Radiation was first used for the treatment of cancer in 1896 by Dr Emil Grubbe and it took the first half of the 20th century for scientists to make the important first steps towards treatment planning and delivery, including dose management to treat cancer more efficiently. The very basic principle of radiotherapy is to aim a high energy radiation beam at a group of cancer cells with the intention of causing damage to them [1].

Early radiotherapy treatments were limited, to a degree, by the inability to reliably visualize the tumor before and during treatment. Initial localization of tumors was carried out using radiographic images of cross sections of the tumor center or anatomical center of the treatment site. With conventional x-rays soft tissues such as tumors were difficult to distinguish and treatment planning was also carried out manually by trained individuals [2]. By the 1960’s treatment planning had progressed slightly to include radiographic images and 2-dimensional planning. The 1970’s saw one of the biggest changes in treatment planning and thus treatment accuracy as high-speed fan-beam diagnostic computed tomography (CT) became more widely used [3]. Patient-specific three-dimensional treatment planning arrived and dose escalation and side effect reduction were possible with better dose conformity.

Historically, treatment planning relied on pre-treatment two-dimensional (2-D) imaging using the radiotherapy beam, with additional margins added around the target to compensate for anatomical changes. While this ensured tumor coverage, it also resulted in unnecessary irradiation of healthy tissue [4]. Using a high-energy radiotherapy beam as an imaging source produced very low-contrast images that were difficult to interpret. Helical tomotherapy, the first 3-D image-guided treatment technique, pioneered a CT-scanner gantry configuration to both deliver radiation and lower the beam energy for imaging and to improve tissue contrast with CT reconstruction [5].

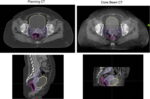

In response conventional radiotherapy units began being equipped with flat-panel image systems that could provide a volumetric CT scan with a single slow rotation around the patient. These systems were called cone-beam CT (CBCT) scanners and were also implemented to provide image-guidance during surgery. As pre-treatment imaging technology advanced, it became clear that patient anatomy and tumor geometry were more dynamic and complex than previously understood, with changes such as organ deformation, tumor shrinkage, and weight loss significantly impacting dose distribution. It should be noted that image-guidance with x-rays adds a small additional exposure to healthy tissue increasing patient risk for a future additional cancer slightly and, in some cases, the imaging dose should be incorporated into the total treatment dose [6].

In an era increasingly focused on healthy tissue sparing, relying on large margins was no longer acceptable. A small additional imaging dose to the treatment area saved a much larger radiotherapy dose to the healthy tissue near the tumor. Adaptive radiotherapy, therefore, emerged as a solution, enabling treatment plans to be adjusted in response to these anatomical changes [7,4].

Adaptive radiotherapy

Modern adaptive radiotherapy can be defined as a form of radiotherapy where the dose delivered is monitored to ensure that it is clinically acceptable during treatment and modifications are made where necessary to minimize the dose to healthy tissue, organs at risk and ensure maximum dose is delivered to the target [8].

Adaptive radiotherapy can be separated into 3 subcategories: offline, online and real-time.

Offline adaptive radiotherapy follows the process whereby treatment is delivered and the treatment plan is updated after using re-simulation, recontouring and replanning in a process that mimic that of the initial treatment planning process.

Online adaptive radiotherapy in comparison, adapts a radiotherapy plan immediately before treatment using image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT)-derived images acquired in the treatment position. Online adaptive radiotherapy has been in use since the 1990’s however it took decades for it to become standard practice due to slow advancements in computer technology, networking and optimization algorithms [9].

Real-time adaptive radiotherapy is an advanced cancer treatment technique that continuously monitors the patient’s anatomy during treatment and dynamically adjusts the treatment beam to track the tumor and optimize dose delivery whilst minimizing dose to healthy tissue [10].

Online adaptive radiotherapy (Online ART)

As adaptive radiotherapy moved more towards online status, where treatment planning is repeated immediately before daily treatment delivery, we have seen clear benefits in head and neck treatments, as well as gastrointestinal, SBRT, pelvic and locally advanced lung cancers [7]. With the ability to account for daily organ movement, filling changes, respiration and peristalsis, there has been a greater ability to spare organs at risk (OAR) and optimize target volumes. This has also facilitated margin reductions, hypofractionation and safer re-irradiation [11].

What has greatly assisted the progression of online adaptive radiotherapy has been improvements in artificial intelligence, this has greatly decreased the amount of human time and resources needed to support this throughout a department. Adaptive radiotherapy is not only about the ability to visualize anatomy and tumors better but also the ability to rapidly and accurately plan treatments. Current treatment planning involves the use of medical imaging, usually CT scans, to obtain the patient’s anatomy, then designing customized beam arrangements, geometry, intensity and modulation during plan optimization [4]. With online ART the ability to do all of this whilst the patient is on the treatment bed awaiting treatment adds a level of pressure, requires additional training of multiple treatment staff and results in the patient being on the treatment couch for longer which impacts on daily workflow.

The frequency in which adaptive radiotherapy is used for one individual patient can be adjusted depending on the rate of anatomical changes in and surrounding the tumor site. Some regions of interest show slow anatomical changes so less frequent ART is needed and others have more random variations in anatomical changes so would need more frequent ART [4]. Offline ART might be acceptable for patients with more stable OAR and slow tumor responses. These would help alleviate some pressure from departments struggling with resources [7].

Studies are still limited on how advantageous online adaptive can be for certain tumor sites; often, data is selected from offline adaptive studies. It is these studies that have observed the significant anatomical changes seen with head and neck cancer as treatment progresses. One study found a 90% primary and 60% nodal gross tumor volume reduction by week 4 of radiation therapy. The significance of this is potential harm to particularly radiosensitive structures and organs such as the parotid glands, damage to these has the potential to cause lifelong complications for the patient [12].

A current drawback of online ART is the additional time needed to undertake imaging and planning before beam-on, which means longer in the treatment room for patients. In a study by Avkshtol et al [12] they investigated the implementation of online ART for head and neck patients, into a department that currently did not use this technique. They found that whilst the additional time was well tolerated, there was still room for optimization and there needed to be an expected learning curve as this was a new technique implemented in department.

Technologies supporting online adaptive radiotherapy

Online ART is an advanced technique in radiotherapy, and one of the identified barriers to its implementation is a shortage of human resources. Its progression into departments was slowed by the identification of critical gaps in training and skill development in departments.

Currently, online ART is supported by technologies with 3 different imaging modalities, MR-based, CBCT-based and PET-based [4]. The Elekta Unity was showcased as a huge step forward for online adaptive techniques as it showed unparalleled soft tissue contrast and visibility when compared to CBCT use in online adaptive radiotherapy as well as zero additional radiation dose. However, the introduction of this brought with it an imaging technique that is not in standard radiation therapy training, therefore extensive training is needed to achieve competence and proficiency in it. A UK-wide training analysis revealed that of the radiation therapists (RTT’s) asked, only 3% reported having knowledge and experience in MRI contouring and 7% in image acquisition. Therefore, the introduction of MR-guided radiotherapy required very specific and extensive training which included: MR safety, MR image acquisition and optimization, MR image interpretation and adaptive radiotherapy strategies [13].

Traditionally, CT-based image-guided treatment planning and verification is carried out by RTT’s. As MR-imaging was introduced into radiotherapy with the creation of the MR-Linac, there became a need for radiation oncologists, medical physicists and RTT’s to all be present for treatment delivery. This results in a drain on resources and a decrease in the number of treatments per day. Moreover, there are several stressors commonly reported with MR-linac systems, such as noise, confined spaces, and heat [14].

When considering the additional staffing and extensive training requirements, it is important to recognize that geographical disparities in advanced radiotherapy training has already been identified. RTTs working in less developed regions often lack access to the necessary resources to participate in specialized training. This results in a significant skills gap [11], which further limits the adoption of online adaptive therapy—particularly when combined with the substantial financial investment required to acquire the technology.

CBCT-based online adaptive radiotherapy

The radiation dose associated with CBCT has long been recognized as a drawback of using this modality for treatment verification in radiotherapy. A bigger concern is the comparatively poor image quality of CBCT relative to high rotation speed fan-beam CT or MR, which poses challenges when considering its use for online ART. The main reason for poor image quality is organ motion during the slow rotation of the imaging system which causes artifacts that make the images hard to interpret and difficult to use as a basis to compute the radiation therapy dose distribution.

Despite these disadvantages, CBCT offers a key advantage: accessibility. It is already widely available in most radiotherapy departments for routine treatment verification, and training in its use is typically included in standard departmental programs. Consequently, the introduction of CBCT-based online ART mainly requires ensuring that sufficient staff are available and trained to generate treatment plans quickly and efficiently while the patient remains on the treatment couch. Emerging technologies, such as the Varian Ethos™, integrate artificial intelligence and machine learning to streamline this process and reduce image motion artifacts, enabling physicians to rapidly select either the reference plan or an adapted treatment plan during the same session [9].

PET-based adaptive radiotherapy

PET-based online adaptive radiotherapy is currently only in use in research and in some clinical trials. A study by Li et al [15] investigated the clinical feasibility of PSMA-PET imaging in adaptive SABR workflows for high-risk prostate cancers. The study supported the use of biology-guided radiotherapy when implemented using standard ART platforms such as MR-Linac and CBCT-based treatment machines. They expressed clear benefits the PET-image can bring, extending beyond anatomical landmarks to using actual biomarkers of the patient to plan treatment [15]. The downside to PET-based adaptive radiotherapy is the need for daily preparatory injections of an expensive radioactive tracer 45 to 60 minutes before treatment thereby tripling to quadrupling the average session time to the patient. The radiotracer also adds whole-body dose burden larger than that of CT and these systems also require a CT to help interpret the PET scans.

Emerging technologies

The next step forward for online adaptive radiotherapy (ART) is the integration of a pre-treatment imaging modality that has long been central to radiotherapy: diagnostic-quality, high-rotation-speed fan-beam CT. While CT already plays a significant role in offline adaptive radiotherapy, it has not yet been widely adopted in online adaptive workflows, primarily because conventional technologies have struggled to successfully integrate CT scanners into the treatment room.

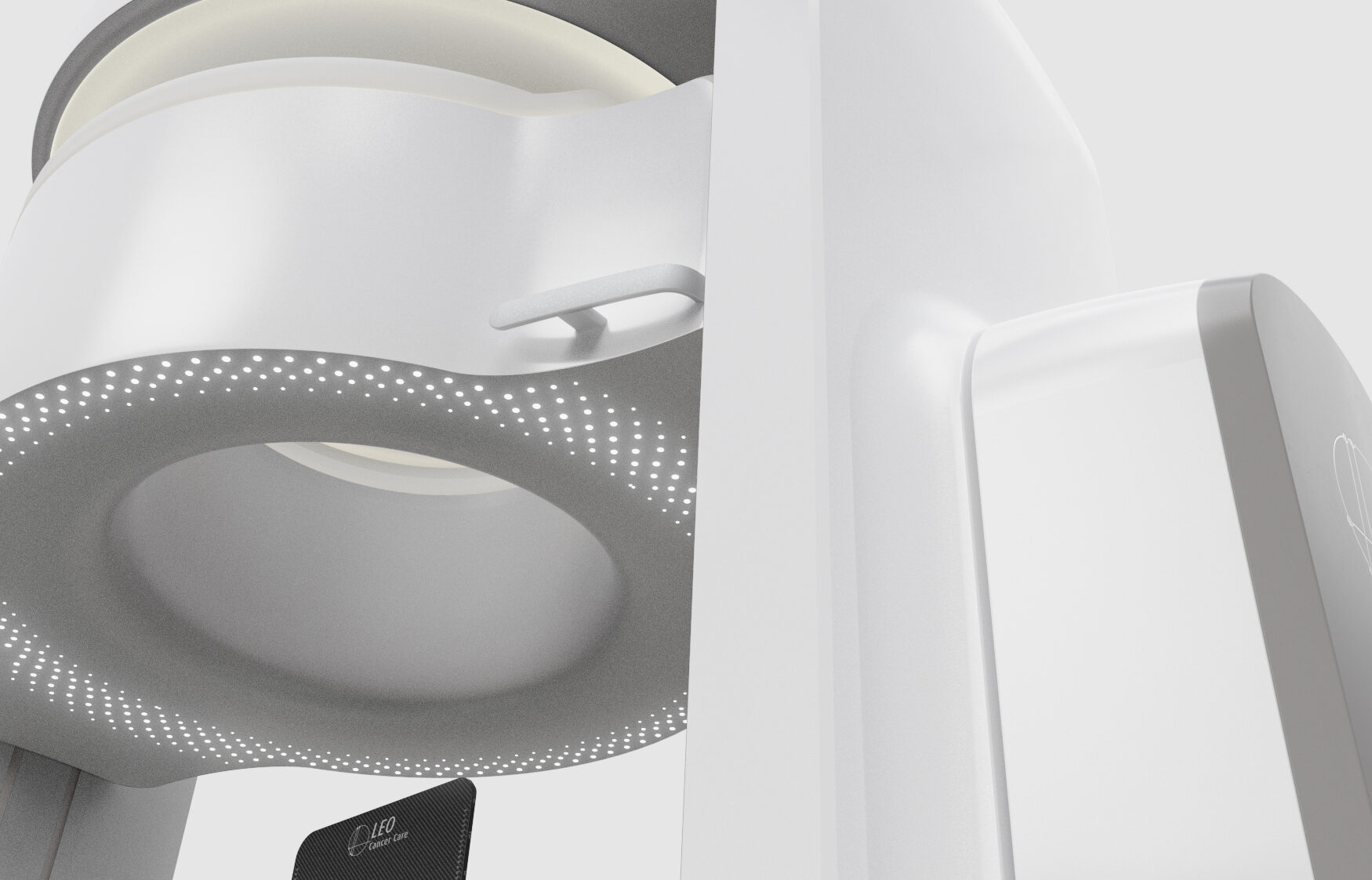

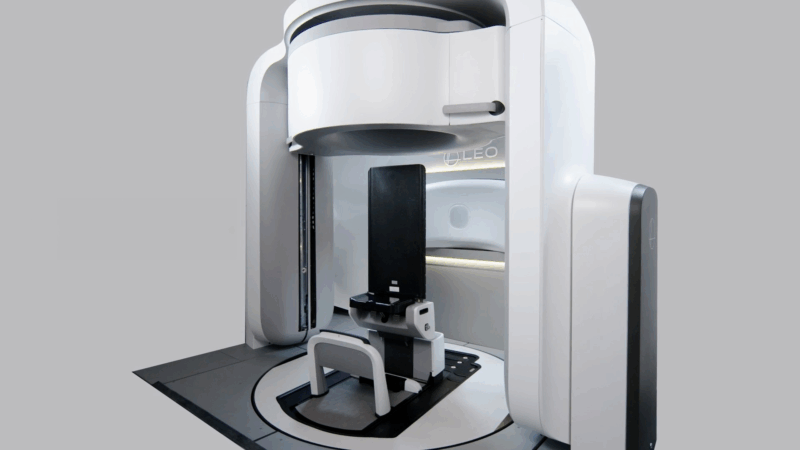

Leo Cancer Care, a company developing upright radiotherapy solutions, has recently received FDA clearance for its upright treatment system featuring an integrated upright high-speed fan-beam CT scanner. This innovation provides a unique opportunity to deliver online adaptive treatments using the same motion-artifact-free imaging modality employed during initial planning, ensuring image consistency across the patient pathway. The pre-treatment image could be used as the planning image online treatment or before the next treatment session.

Several advantages are associated with this approach. Radiation therapists are already proficient in CT image acquisition, as it forms a core element of their professional training. Treatment planning using CT data is standard practice and established departmental training frameworks can be readily adapted and utilized. As a result, implementation of CT-based online adaptive workflows could be streamlined, facilitating faster clinical adoption through widespread familiarity with both the imaging modality and associated planning systems. From a patient perspective, benefits include the familiarity of CT imaging, a lower imaging radiation dose compared with cone-beam CT (CBCT)-based online ART, and the avoidance of the stress associated with MRI-guided treatment setups.

Preliminary research into upright radiotherapy has also identified a clear patient preference for treatment in an upright position, with many individuals reporting greater comfort and improved ease of access to and from the treatment position compared with supine couch-based setups [16]. Feasibility studies have further demonstrated physiological advantages of upright positioning, including enhanced organ stability during pelvic treatments [17] and reduced organ drift, such as diminished liver motion, compared with supine positioning [18]. These early findings suggest that upright radiotherapy may reduce organ movement and tumor motion, providing more reproducible and stable positioning across treatments.

This motion stability has significant impact on ART workflows. Adaptation in radiotherapy can be divided into two groups:

1. Adaptations driven by setup deviations or anatomical changes, such as weight gain/loss or variations in organ filling.

2. Adaptations driven by changes in the target volume, including tumor growth or shrinkage, which require physician review.

The majority of adaptive interventions belong to the first group and typically do not require real-time oncologist approval. If upright positioning reduces the frequency of these setup-driven adaptations, the clinical burden of online ART could be substantially reduced. In such a model, only the smaller second group; cases involving genuine biological change, would need physician-led review. This approach would relieve resource pressures, minimize time spent in the treatment room, and improve workflow efficiency without compromising patient safety.

Together, these findings highlight the potential for upright CT-based radiotherapy systems to enhance the delivery of online adaptive treatments. Reduced organ motion could lessen the need for frequent imaging and replanning, while integrated CT technology offers higher image quality and lower radiation dose than CBCT.

As the field continues to evolve, a critical question remains: Is online adaptive radiotherapy worth the additional expense, resources, and time—and does upright CT technology hold the key to making its clinical integration more efficient and achievable?

References

1. Skliarenko J, Barry, A. Clinical and practical applications of radiation therapy: when should radiation therapy be considered for my patient? Medicine. 2020. 48 (2):84-89,

2. Kim, D.W, et al. History of the Photon Beam Dose Calculation Algorithm in Radiation Treatment Planning System. Medical Physics. 2020; 31(3): 54-62

3. Huh H, Kim, S. History of Radiation Therapy Technology. Progress in Medical Physics. 2020; 31(3): 124-134

4. Lemus OM, Cao M, Cai B, Cummings M, Zheng D. Adaptive Radiotherapy: Next-Generation Radiotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Mar 19;16(6):1206. doi: 10.3390/cancers16061206. PMID: 38539540; PMCID: PMC10968833.

5. Mackie TR, Holmes TW, Swerdloff S, Reckwerdt PJ, Deasy JO, Yang J, Paliwal BR, Kinsella TJ, Tomotherapy: A new concept in the delivery of dynamic conformal radiotherapy. Med. Phys. 20, 1709-1719 (1993).

6. Wilson L, et al. Cone beam CT dose optimization: A review and expert consensus by the 2022 ESTRO Physics Workshop IGRT working group. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2025. 209: 110958

7. McComas KN, Yock A, Darrow K, Shinohara ET. Online Adaptive Radiation Therapy and Opportunity Cost. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2022 Oct 26;8(3):101034. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2022.101034. PMID: 37273924; PMCID: PMC10238262.

8. Dong B, et al. Key technologies and challenges I online adaptive radiotherapy for lung cancer. Chinese Medical Journal. 2025; 138(13). Pp1559-1567

9. Liu H, et al. Review of cone beam computed tomography based online adaptive radiotherapy: current trend and future direction. Radiat Oncol. 18, 144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-023-02340-2

10. Keall P, et al. Real-Time Dose-Guided Radiation Therapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology. Biology. Physics. 2025. 122 (4):787-801,

11. Shepherd M, Joyce E, Williams B, Graham S, Li W, Booth J, McNair HA. Training for tomorrow: Establishing a worldwide curriculum in online adaptive radiation therapy. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2025 Feb 5;33:100304. doi: 10.1016/j.tipsro.2025.100304. PMID: 40027119; PMCID: PMC11868997.

12. Avkshtol V, Meng B, Shen C, Choi BS, Okoroafor C, Moon D, Sher D, Lin MH. Early Experience of Online Adaptive Radiation Therapy for Definitive Radiation of Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023 Apr 26;8(5):101256. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2023.101256. PMID: 37408672; PMCID: PMC10318268.

13. Hogan L, et al. Old dogs, new tricks: MR-Linac training and credentialing of radiation oncologists, radiation therapists and medical physicists. J Med Radiat Sci. 2023 Apr;70 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):99-106. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.640. Epub 2022 Dec 11. PMID: 36502538; PMCID: PMC10122927.

14. Westerhoff JM, et al. On Patient Experience and Anxiety During Treatment With Magnetic Resonance-Guided Radiation Therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024 May 4;9(8):101537. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2024.101537. PMID: 39035171; PMCID: PMC11259694

15. Li R, et al. Clinical Implementation of PSMA-PET Guided Tumor Response-Based Boost Adaptation in Online Adaptive Radiotherapy for High-Risk Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 2893.

16. Boisbouvier S, Boucaud A, Tanguy R, Grégoire V. Upright patient positioning for pelvic radiotherapy treatments. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2022 Nov 28;24:124-130. doi: 10.1016/j.tipsro.2022.11.003. PMID: 36471684; PMCID: PMC9719023.

17. Schreuder AN, Hsi WC, Greenhalgh J, Kissick M, Lis M, Underwood TSA, Freeman H, Bauer M, Towe S, Mackie R. Anatomical changes in the male pelvis between the supine and upright positions-A feasibility study for prostate treatments in the upright position. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2023 Nov;24(11):e14099. doi: 10.1002/acm2.14099. Epub 2023 Jul 24. PMID: 37488974; PMCID: PMC10647982.

18. von Siebenthal M, Székely G, Lomax AJ, Cattin PC. Systematic errors in respiratory gating due to intrafraction deformations of the liver. Med Phys. 2007 Sep;34(9):3620-9. doi: 10.1118/1.2767053. PMID: 17926966.

19. Hoskin P, Alonzi R. Imaging for Radiotherapy Planning. 2016. In General Radiology. Available at: https://radiologykey.com/imaging-for-radiotherapy-planning/ [Accessed Online: 10/12/25]

20. Tyagi N, et al. Daily Online Cone B. Daily Online Cone Beam Computed Tomography to Assess Interfractional Motion in Patients with Intact Cervical Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2011. 80(1): 273-280

21. American Association of Physicists in Medicine. What is An MR-Linac. Available at: https://www.medicalradiationinfo.org/radiationandmedicine/radiation-therapy/mr-linac/ [Accessed online 10/12/2025]

Subscribe to our newsletter

STAY CONNECTED

Get the latest updates and exclusive offers delivered straight to your inbox

Subscribe